Einstein’s Courageous Speech at Lincoln University: Confronting Racism in America

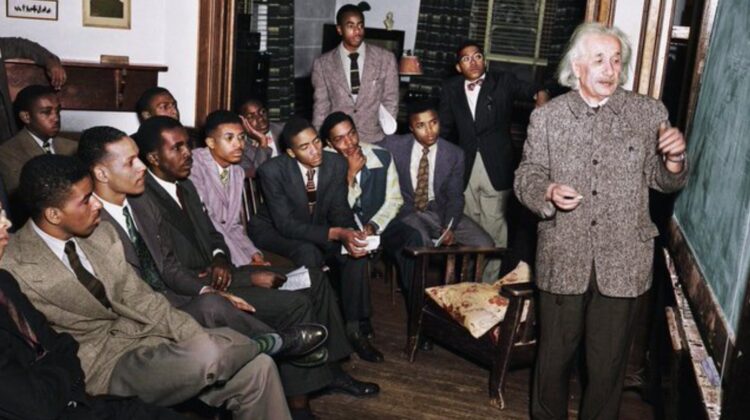

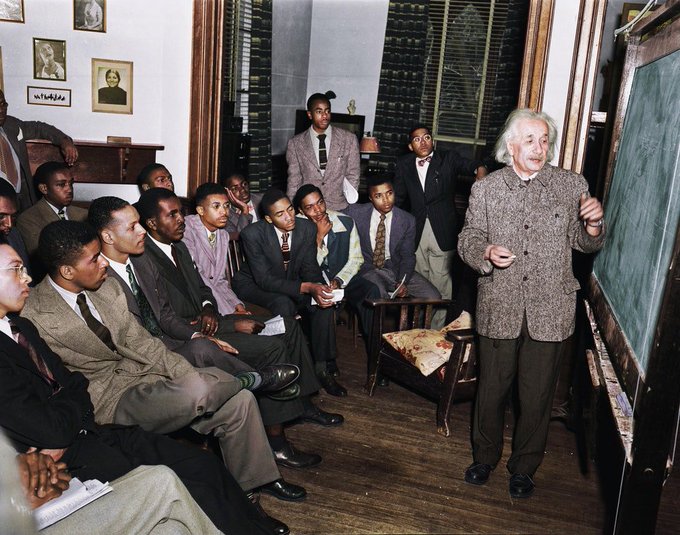

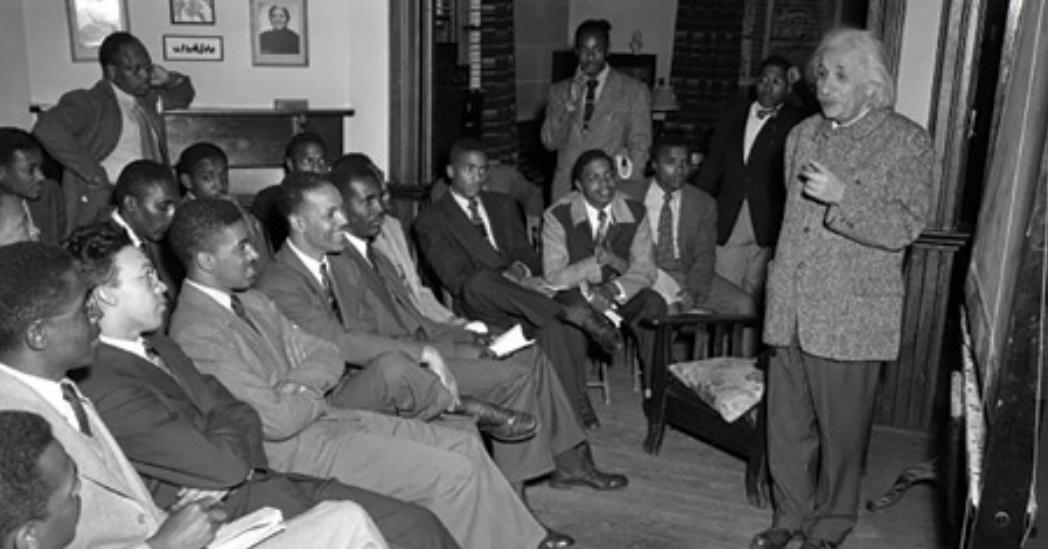

Albert Einstein is known for his groundbreaking work in physics, but he was also an outspoken advocate for social justice. In May 1946, he broke his self-imposed rule of not speaking at universities for nearly two decades to give an address and accept an honorary degree from a small, traditionally black university near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania called Lincoln University.

Einstein had moved to Princeton in 1933 to escape the coming Holocaust in Europe, but he found that racial segregation was still prevalent in America. While Einstein was an exception, blacks and Jews were generally not welcome in Princeton. As late as September 1942, the Princeton Herald explained that admitting black students to the university, while morally justified, would be too offensive to the large number of Princeton’s southern students.

At the end of World War II, black soldiers returned home after fighting for freedom and democracy, but they found themselves facing a newly hostile American populace. A wave of anti-black violence began in 1946, resulting in 56 African-Americans dead, mostly veterans. Racial segregation was the rule in most of America in May 1946, with separate and unequal public and private facilities from housing and schools to buses and beaches not only throughout the South but also in many other parts of the country.

One of the most publicized instances of white resistance to black notions of equality forged in World War II occurred in February 1946, when five hundred Tennessee state troopers with submachine guns surrounded the African-American community of Columbia, Tennessee. The trouble started when a black Navy veteran accompanied his mother to a radio store to complain about a botched repair job. The white repairman (also a veteran) followed him and his mother out of the store, and attacked them as they left the building. Although the black veteran was struck first, he was arrested and jailed on a charge of attempted murder. Hostilities quickly escalated.

More than one hundred black men were arrested. Twenty-seven were charged with rioting and attempted murder and two were shot awaiting bail in the local jail. The riot made national headlines.

Three months later, Thurgood Marshall came to town as the lead attorney for the defense. He barely escaped being lynched himself. Einstein publicly joined the “National Committee for Justice in Columbia, Tennessee,” which was headed by Eleanor Roosevelt.

Einstein’s speech at Lincoln University was not a coincidence. He declared: “The separation of the races is not a disease of colored people, but a disease of white people. I do not intend to be quiet about it.” But according to Fred Jerome, who has written extensively on Einstein’s collaboration with the organization “The American Crusade to End Lynching,” the press largely ignored this speech, letting it sink into “a historical black hole.”

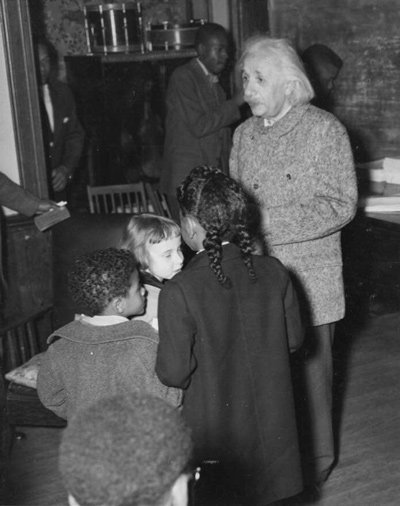

Einstein with the children of Lincoln University Faculty, May 3, 1946

Einstein showed great courage in saying and doing what others would not. As he explained in his Lincoln University speech:

“There is … a somber point in the social outlook of Americans … Their sense of equality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skins. Even among these there are prejudices of which I as a Jew am dearly conscious; but they are unimportant in comparison with the attitude of ‘Whites’ toward their fellow-citizens of darker complexion, particularly toward Negroes. … The more I feel an American, the more this situation pains me. I can escape the feeling of complicity in it only by speaking out.”

Speaking out in the face of injustice, torture, oppression, and genocide is still something every American can do. And determining what is not said is as critical as listening to what is. Einstein’s ability to see what was not obvious and to share these insights with the world made him such a great man.